By Axel Threlfall and Michelle Nichols

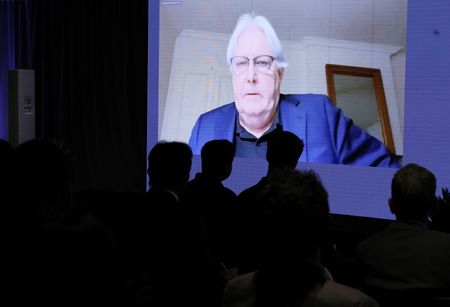

NEW YORK (Reuters) -The United Nations will ask for 25% more money in 2023 to fund humanitarian aid operations globally, the U.N. aid chief told a Reuters NEXT event on Wednesday, where he also warned that while famine would not yet be declared in Somalia, people were already dying there of hunger.

The United Nations had appealed for a record $41 billion to provide life-saving assistance for 2022 and is due to launch its appeal for 2023 on Thursday.

“It’s going to go up by about 25% and that’s a shocker,” U.N. aid chief Martin Griffiths said without giving specific figures. “It’s gone up about each year by about 25% in recent years … the gap between needs and funding is going to grow.”

He said that in 2022 the United Nations had only received about 44% of the money needed, adding: “In years gone by, we’ve seen 60-65% as a norm.”

Griffiths said the gap between funding and needs was growing because of the “knock-on effects of the last couple of years” from events like the war in Ukraine, conflict, the COVID-19 pandemic and other crises, like a spike in cholera outbreaks.

He predicted that the gap would be bigger in 2023 and “frankly we are going to continue to fail, in many more countries, the high numbers of people that we serve and we serve roughly a population which is equivalent to about the third-most populous nation in the world.”

“It’s a staggering and somewhat ludicrous responsibility,” Griffiths added.

SOMALIA HUNGER

In Somalia, the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) – used by U.N. agencies and aid groups to determine food insecurity – in September projected a famine in two districts in Somalia. The IPC is expected to issue a new analysis of the situation in the coming weeks.

Griffiths said that he understands that a famine will not yet be declared in Somalia, but he warned: “We can assume that in Somalia and soon in Ethiopia, where the numbers will be much worse … people are dying already of hunger and starvation.”

Famine has been declared twice in the past 11 years: in Somalia in 2011 and in parts of South Sudan in 2017.

“Half the people who died in Somalia died before the famine was declared,” International Rescue Committee President David Miliband told the Reuters NEXT event. “Why aren’t we taking action now because we know the deaths are starting now.”

The most extreme warning by the IPC is phase 5, which starts with a catastrophe warning and rises to a declaration of famine in a region.

Somalia’s drought envoy, Abdirahman Abdishakur also told Reuters that the humanitarian community had said the threshold for a famine had not yet been met, but that “they told the government that a famine will be declared, maybe in a few months, if the rains fail again.”

For famine to be declared, at least 20% of the population must be suffering extreme food shortages, with at least 30% of children acutely malnourished and two people out of every 10,000 dying daily from starvation or from malnutrition and disease.

“If they have the data and examine it and they decide the threshold has been met then the Somali government is not against famine (declaration). But the threshold must be met and it hasn’t,” Abdishakur said. “There are no politics in this, it is only data.”

To view the Reuters NEXT conference live on Nov. 30 and Dec. 1, please click here.

(Additional reporting by Tommy Wilkes in NairobiWriting by Michelle Nichols, Editing by Nick Zieminski)